What is intestate succession?

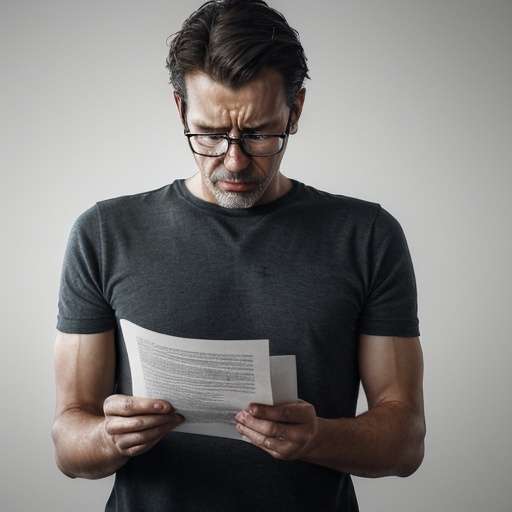

If a person who dies does not have a will, then the person is said to have died intestate. This means that the person’s assets and liabilities are handled by the intestate laws of the province where the deceased resided – when he/she died. The intestate laws vary from one jurisdiction to another. Typically, if the person dies without a will, their assets are frozen until the court combs through every detail of their estate to make a decision regarding the manner in which a person’s possessions will be allocated. For the ones you leave behind, this process can be time-consuming, exhausting and usually involves more money spent wrapping up your affairs – all of which is easily avoidable. More importantly, dying intestate means that the wishes of the person who died may not be fulfilled. Many practical issues such as providing for children with special needs may not be addressed.

In short, not having a will means losing control over some of the most important decisions a person will ever have to make. Wills are important because they let a person choose who gets their assets when they die – saving time and headaches for loved ones.

Which items don’t pass through a will?

First, it is important to note the many assets do not pass through a will. This is especially true if the assets were properly titled. To determine how the property was titled, the original documents will need to be located. Typically, these documents are in a safe deposit box or a strong box. Some of the assets where a will would not make a difference are:

- Life insurance proceeds. These assets are payable to the people named as beneficiaries

- Assets held as tenants held jointly or as tenants by the entirety. Assets such as homes that are owned by a husband and wife are normally held as tenants by the entirety – which means when the first spouse dies the home automatically goes to the surviving spouse.

- Community property with right of survivorship. In community property states, property held with right of survivorship is similar to joint property and tenants by the entirety property. The assets go to the survivor without any need for a will.

- Some retirement benefits. RRSP and some other retirement plans are paid to the named beneficiary.

Who handles the estate?

One of the main reasons for having a will is deciding who will manage the estate. The person who handles the administration of the estate is normally a trusted person who is good at money management and at meeting deadlines while also respecting the needs of the family members and beneficiaries. A spouse or a child can be named an executor. A non-relative or even a non-person such as a bank can be appointed executor.

It there is no will, the deceased hasn’t set out their wishes for who they trust to distribute or manage their estate. This means the court has to authorize someone to close the financial affairs of the person who dies and make sure their assets are distributed correctly. Anyone who is eligible can request approval from the court. If more than one eligible person applies, then the court will decide which person will be the administrator. The person who will become the estate trustee is usually determined by their relationship to the deceased. This begins with the deceased’s spouse (including common-law spouse), then children, then next of kin in decreasing order.

If the person who applies to be named trustee has a lower right to that role than another person, the higher-ranking person must renounce their right to apply for the certificate. For example, if the deceased’s daughter wants to apply for the certificate but the deceased had a surviving spouse, the spouse must renounce their right to apply.

Certain provinces may have rules about the applicant’s residency. If the deceased lived in Ontario, for example, the trustee must also be an Ontario resident.

Executors and administrators are commonly called the personal representative. The personal representative is required to collect all the assets that pass through the estate; pay all the taxes, administrative fees, and creditors; and then distribute the balance of the money to the rightful heirs.

Who is entitled to the assets?

Each province has their own set of laws that determines who gets the estate assets and in what amounts – if there isn’t a valid will.

The primary beneficiaries are the spouse or a domestic partner and the children. If the deceased was single without children, then blood relatives such as parents and siblings (if still alive) are generally next in line to inherit. In the rare instance that there is no one to whom your estate can be left, your estate may end up going to the provincial government.

Most provinces also except specific people from inheriting such as anyone who contributed to the death of the deceased. Parents who abandon their child or didn’t support their child may not be entitled to inherit if the child dies.

The province of residency is normally where the decedent had his/her home or apartment when the death occurred. Someone who lived the last 10 years of their life in Ontario but dies while on vacation in Florida will normally be considered a resident of Ontario and Ontario intestate laws will apply.

Some intestate terms

Here are a few relevant intestate succession terms:

- Issue and issue per stirpes. Issue, in estate law, usually means the line of descendants of a person. It can get confusing. Here’s an example. John’s spouse dies before John and the couple had three children – Sue, Dave, and Larry. If the children are all alive when their father dies, then each child would in most, if not all, jurisdictions each get 1/3 of John’s assets. What If, however, Larry is deceased when his father dies but Larry had two children Karen and Fred. Then, the issue of John would be Sue, Dave, Karen, and Fred. Typically, the intestate laws of most states would say that the issues get their money per stirpes (essentially through their parents). So, Sue and Dave would still get 1/3 each and Karen and Fred would equally divide Larry’s 1/3 share and get each get 1/6 of John’s estate

- To qualify as a spouse, the couple must have been legally married at the time of death. Intestate laws do govern the following changes and exceptions. Each province is different.

- Divorced. If the parties were officially divorced when the other spouse died, then the ex-spouse is not eligible. If the parties are in the middle of a separate but not yet divorced, the courts could still see the estranged spouse as eligible. It may depend on if the couple was legally separated.

- Common-law marriage. Some jurisdictions allow a common marriage based on factors such as the length of the relationship and whether and how the couple held themselves out to the public as married.

- Same-sex marriage. This depends on the current federal and provincial laws and whether the couple had followed through with the marriage requirements.

- Children born by the father or mother are entitled to inherit from the mother. The issue can get complicated in the following cases:

- Adopted children. Generally adopted children are treated exactly as biologically born children and they are entitled to inherit from their adoptive parents. However, if a child is adopted that severs the relationship the child had with his/her biological parent. The adopted child doesn’t inherit from both sets of parents – just the newly adopted ones.

- Stepchildren. Unless the new spouse adopts the children of his/her spouse, stepchildren do not inherit assets from their stepdad or stepmom. Some provincial exceptions may apply.

- Foster children. Normally, foster children do not inherit from the adults taking care of them.

- Children born after the parent dies. If conception occurred before the deceased died but the child is born after the parent’s death, then this child also inherits through his parents. Death doesn’t change the child’s rights.

- Children born out of wedlock. In most jurisdictions, the child will still inherit from his parents. Proof of paternity will likely be required to inherit from the father.

- As with children, the right to inherit depends on the province’s intestate succession laws. Half-siblings may inherit from their other half-sibling, if the person who died was unmarried and without children or parents.

Additional issues

Intestate laws usually fail to consider special circumstances such as:

- Minor children. In a will, if there are minor children, the testator can appoint a guardian of the person to raise the child and a guardian of the minor’s property to handle the child’s share of the assets. Without a will, these guardians (who can be the same person or can be different) are appointed by the judge. The people who wish to serve as guardians will request that the judge approve their appointment. The judge will consider a lot of factors include the relationship of the person making the request, the family circumstances, and the best interest of the child; however, the court will make the decision without your input.

- Survivorship requirement. Each province has its own laws, or may follow the Uniform Simultaneous Death Act), to cover the scenario where an heir such as a spouse dies at the same time as his/her spouse or within a few days. Many wills have a 60-day survival requirement.

- Financially assisted persons. If you are financially supporting an elderly parent or paying for a grandchild’s education that aid could be discontinued by your court appointed trustee.

While every province’s law is designed to do what is in the best interest of a descendent, the only way to avoid your assets falling into the wrong person’s hands it by prioritizing your estate planning today while you are still able. Only you know how you want your estate to be distributed when you die and simply telling someone is not sufficient. Your wishes need to be in writing. At LegalWills.ca, you can create a customizable, province-specific will from the comfort of your own home in just 20 minutes.

- Probate in Canada – What it is, what it costs, how to reduce fees. - January 6, 2025

- All about Trusts – how to include a Trust in your Will - June 9, 2022

- The Holographic Will – what is it and when should you use one? - May 18, 2022